Underground petroleum contamination is a widespread problem that drains public resources and has been routinely mismanaged to the detriment of public safety and environmental integrity. The first of many steps that should be taken to address this problem is banning the construction of new gas stations.

A central fixture of American street corners, one that’s synonymous with automobiles, road trips and the luxury of unbridled movement, is becoming increasingly obsolete: gas stations. In a market environment where electric vehicles dominate and continue their exponential growth, up to 80% of the current fuel-retail market may be unprofitable in 12 years, according to the Boston Consulting Group.

But gas stations aren’t just a failing business model — they’re detrimental to both human and environmental health, and are a burden on taxpayers who often inadvertently fund efforts to clean up what is a widespread problem of underground petroleum contamination.

Gas stations are a severe liability largely due to leaking underground storage tanks (LUSTs). Typically, gas stations have two or three of these giant, submarine-shaped USTs, each of which can hold tens of thousands of gallons of petroleum and its many hazardous components, including methyl tertiary-butyl ether (a suspected carcinogen), lead (a neurological inhibitor), benzene (a known carcinogen) and several others.

Undergound storage tanks (USTs) leak when the tank, gas pump, or connecting pipes corrode over time. Regular, mandated inspections could mitigate the damage from leaks that occur unnoticed for years, but when USTs do leak, these chemicals pollute a wide area even in small quantities. For instance, a 10-gallon leak has the potential to contaminate 12 million gallons of water. Given that 115 million Americans rely on groundwater for drinking water, 45 states have designated USTs as a major threat to groundwater quality.

These chemicals are also incredibly persistent. For example, on February 15, 1989, a Franko Oil service station in Eugene reported a UST leak. In 2006, after four USTs were removed along with enough petroleum-contaminated soil to fill over 50 dump trucks, the concentration of benzene in underlying groundwater was still 720 micrograms per liter (µg/l). The Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (MCGL), as defined by the National Primary Drinking Water Regulations, for benzene is 0 µg/l.

As of March 2023, there have been 570,964 confirmed releases from USTs nationwide, including 7,899 releases in Oregon. Through a decades-long remediation campaign, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), alongside state agencies like the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), has cleaned up over 506,000 UST releases to some extent. Costs are not necessarily borne by the polluter.

However necessary, this campaign is imperfect and, by failing to enforce corporate accountability while oftentimes neglecting to restore petroleum-contaminated sites completely, it demonstrates why the construction of new gas stations is harmful to our communities — to everyone except Big Oil.

Consider the history of USTs and how they’ve been regulated.

Following World War II, rapid suburbanization and increased automobile usage heightened the demand for petroleum, leading to the establishment of more USTs. But there was one problem: these USTs were made from unprotected steel, as opposed to the modern fiberglass equivalent, making them extremely prone to developing holes through oxidation.

Big Oil understood this problem as early as the 1930s, and by the 1970s, companies were beginning to internally scramble for a way out. A 1973 report from Exxon said, “The subject of underground leaks at service stations is one of growing concern to petroleum marketers. Large sums of money, time and effort are exhausted on a continuing basis in the location and correction of leaking tanks and lines.”

Rather than taking responsibility for the damage they caused, however, Big Oil unloaded that liability onto small business owners. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Big Oil programmatically disinvested from UST systems and oftentimes neglected to take precautionary actions at stations that were already independently owned.

Today, the National Association of Convenience Stores estimates that convenience stores sell 80% of the fuel purchased in the U.S. and that Big Oil now owns less than 1% of U.S. service stations.

Around that same time, the federal government started implementing regulations. Under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERLA), EPA required leak detection, leak prevention and corrective action plans for all USTs containing hazardous substances beginning in 1988. EPA also required UST owners and operators to demonstrate financial responsibility for taking corrective action, along with compensating third parties for any bodily or property damage caused by leaks, under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act.

Since USTs had been slowly leaking for decades, though, small business owners inherited huge amounts of liability that most had no means of paying for. According to a 2004 survey by EPA, the average cost of cleaning up 95 service stations was $243,299 — which accounting for inflation is $398,530 today. If any remediation technologies are employed, such as pump-and-treat systems or bioremediation, or if groundwater is encountered during the tank removal process, the cost jumps up by hundreds of thousands of dollars.

SeQuential Biofuels, located along McVay Highway, was built above an expensive LUST cleanup site. Previously operating as a Franko Oil service station until bankruptcy in 1991, five USTs were removed in 1996 during which the concentration of benzene in groundwater was detected at a maximum of 33,000 µg/l. SeQuential Biofuels acquired the property from Lane County in 2005, and funded the redevelopment with a $50,000 loan from the Oregon Economic and Community Development Department, a $197,520 EPA Brownfield grant, and a $1.2 million loan from the Oregon Department of Energy.

Excavating petroleum-contaminated soil prior to the construction of SeQuential Biofuels. (DEQ)

Facing exorbitant costs, small business owners intensely opposed EPA’s new financial responsibility requirements. In response, EPA allowed UST owners or operators to demonstrate financial responsibility by either continuing to purchase pollution liability insurance from private companies, or by opting into newly established state financial assurance funds.

36 states currently have these special funds. UST owners or operators opt into these funds by complying with technical requirements, promptly reporting leaks and by paying a nominal yearly registration fee (usually $100 per UST), which is then supplemented by a flat tax on state petroleum sales (usually 0.1 cents per gallon).

Oregon is one of few states that does not have a financial assurance fund. “The majority, around 90%, of our over 1600 facilities in Oregon use the mechanism of insurance to demonstrate financial responsibility,” said Steven Paiko, the UST Permits and Licensing Coordinator for DEQ. The remaining UST owners or operators, said Paiko, opt for self-insurance where they leverage their own funds for cleanup costs, or demonstrate financial responsibility through a mechanism only few are eligible for, such as a guarantee.

While state financial assurance funds provided a lifeline for small business owners, they shift the burden onto taxpayers rather than the oil industry. UST cleanup became a form of publicly-funded financial responsibility: Rather than encouraging service station owners to internalize future environmental costs, these special funds externalize the cost to taxpayers and provide no incentive to take preventative action.

According to the Association of State and Territorial Solid Waste Management Officials (ASTSWMO) State Fund Survey, state financial assurance funds have paid approximately $20 billion to clean up LUST sites over the past 21 years.

Since the cost of fairly-priced pollution liability insurance dwarfed the registration fee for state financial assurance funds, states with these funds effectively drove out the market for private insurance. With a nearly 100% participation rate where established, several of these funds became insolvent in the late 1990s, precipitating yet another regulatory misstep.

Up until that point, most state programs required that LUST sites be remediated to very low, or even non-detect, levels of contamination — but then the paradigm shifted. According to Matthew Small, an EPA Regional Science Liaison, the agency transitioned from asking “How much of the compounds of concern can we clean up?” to asking “How much of the compounds of concern can we safely leave in place?”

Enter Risk-Based Corrective Action (RBCA): EPA’s current framework for LUST sites that attempts to balance maximum risk reduction with finite resources for cleanup. To that end, RBCA places priority on high-risk sites and, for each site, involves identifying the pathways by which humans could be exposed to petroleum contamination, then cleaning up that contamination according to specific risk-based concentrations (RBCs).

Take, for instance, how RBCA was applied in the cleanup process of a former Chevron service station on Franklin Boulevard, where the 515 Apartments now stand. Beginning in 2004, the cleanup included dozens of soil samples, quarterly groundwater monitoring, and removing 11,060 cubic yards of petroleum-contaminated soil along with 568,000 gallons of petroleum-contaminated groundwater.

A view of the former Chevron UST cavity (center) at the 515 Apartment construction site. (DEQ)

After seven years of cleanup and assessments, the concentration of petroleum and ethylbenzene slightly exceeded the RBC for vapor intrusion, meaning that chemical vapors in the soil could seep through cracks in building foundations and contaminate indoor air. The cleanup company, SAIC Energy, Environment & Infrastructure, advised to let the remaining contamination naturally attenuate out of the soil, and DEQ agreed to close the site provided that there would be no residential use on the first floor of structures.

The base of the 515 Apartments is a parking garage. RBCA enabled SAIC and DEQ to expedite site closure by deeming a certain amount of risk acceptable and by assuming that nature will run its course — but what amount of risk is acceptable and why is nature responsible for cleaning up our (Chevron’s) mess?

In discussing the transition to RBCA, Small said, “Although this may be a more economically efficient approach to cleanup, it knowingly accepts some finite cost of the remaining pollution or the associated resource degradation, and in at least some cases the cost may be higher than we realize.”

RBCA is a well-intentioned effort by a resource-strapped EPA to address petroleum contamination on a daunting scale, but it does so by placing environmental health on the back burner. It produces faster cleanups that leave pollution in place and is human-centric. Even though the Chevron on Franklin was adjacent to the Willamette River and underground petroleum plumes can migrate upwards of 500 feet, there is no mention of how the Willamette was impacted in any case reports.

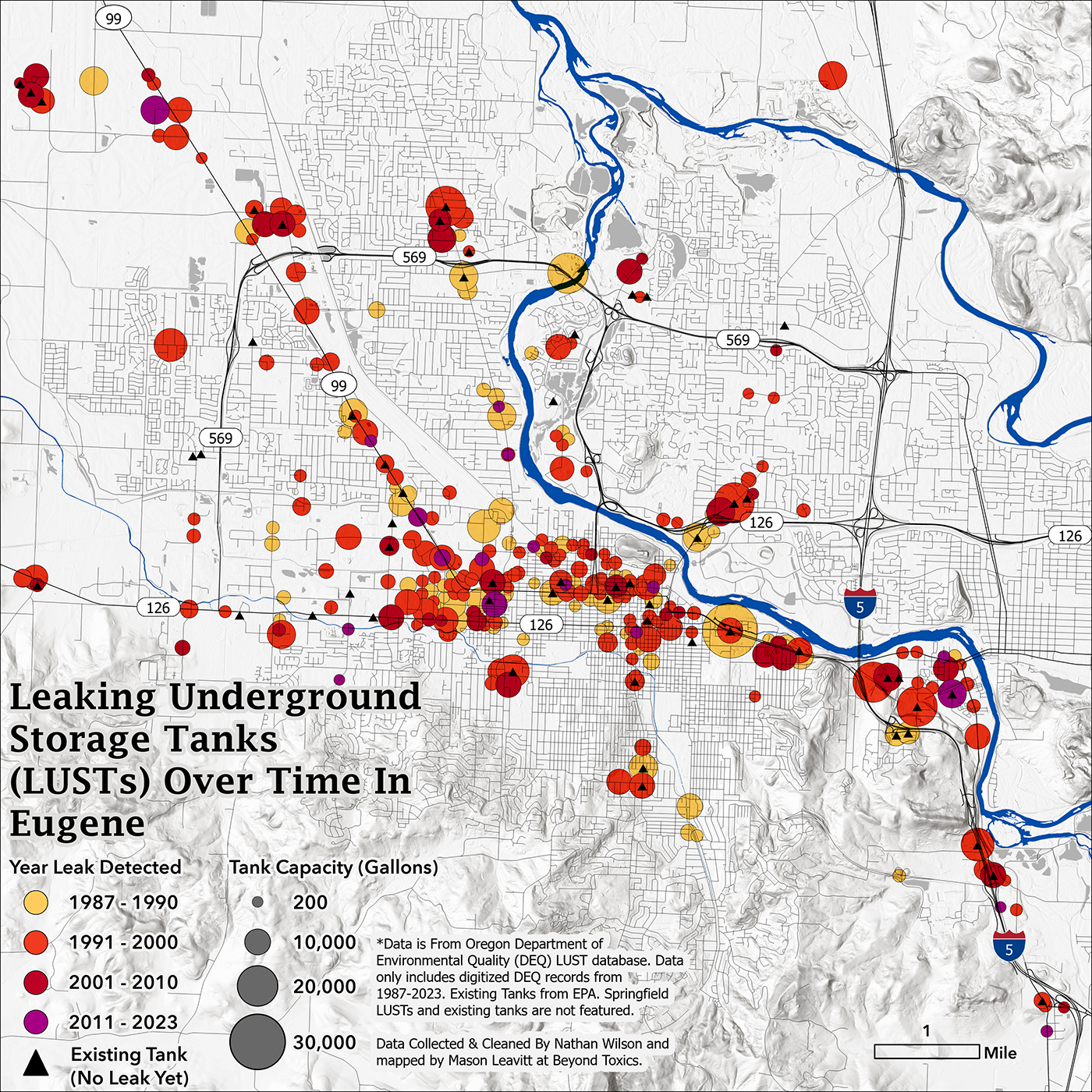

The graphic shows 303 instances of leaking underground storage tanks in Eugene since 1987. Dots are colored by decade the leak was discovered and sized according to the capacity of the tank that leaked. Many are near the Willamette River.

Consider the History of USTs and How They’ve Been Regulated

USTs have a fraught history. When USTs were originally installed, Big Oil was aware of their propensity to leak and avoided incurring that cost by selling gas stations to small business owners. Unable to account for that liability, small business owners advocated that EPA establish state financial assurance funds that were backed with taxpayer money. When state funds became insolvent, EPA transitioned to RBCA so that cleanups would still occur, even if they weren’t completely protective of human or environmental health.

All of this is to say that we don’t need more USTs or more gas stations — especially in cities like Eugene where the majority of residents already live within five minutes of a gas station. There are still 58,483 LUST sites that require cleanup nationwide, including 114 active cleanups in Lane County, with an additional 4,568 leaks reported last year alone.

Everyone inside the city's urban growth boundary (orange line) is able to access one of the city's 56 gas stations within a 5 minute drive. Some can access over 20!

More Gas Stations Will Not Provide Any Benefit to Eugene

Enough is enough. Eugene’s utility predicts that 64% - 80% of passenger vehicles on roads will be electric in 2035, and the Boston Consulting Group estimates 80% of gas stations will be at risk of bankruptcy that same year in cities like Eugene. Gas station infrastructure is staring down the eye of a barrel. Eugene’s residents already have access to at least one of the city’s 56 gas stations within a 5 minute drive. Allowing this industry to expand in the next few years will only equate to more petroleum contamination to clean up. To support a clean energy transition, testify for a moratorium on new gas stations when Eugene City Council votes on the proposal this fall.

By Nate Wilson, Beyond Toxics LUST/UST Data Analysis Intern

Read the Beyond Toxics report, "Beneath The Pump: The Threat of Petroleum Contamination" (PDF)

Read more about our campaign for a gas station moratorium